Selling The Air: The Art of Juan Muñoz

Art has its celebrities, its superstars. The flamboyance and charisma of artists intrigue and exasperate in equal measure. Fame dictates the artist's occupation of history alongside popes and emperors. Likewise, individual works of art are celebrities too. Gormley's stranded figures are rarely seen from the shores of the the sea engulfing them but they have adorned many a Sunday supplement. Guernica is the money shot of countless documentaries. Hirst's diamond-speckled skull is discussed over Islington dinner parties with the same reverance as Katie Price. The Mona Lisa is a poster child. Artworks have their ambassadors.

The work of Juan Muñoz will never enjoy this celebrity status. Whether it be his early puppet figures on distant shelves or the later circus of laughing asiatic statues, Muñoz's pieces are somehow sterilised by their own existence. They will never enter popular culture, neither as priceless hallmarks of good taste nor as the popular gossip-fodder of controversy. As physical creations, they exist in a null void within contemporary western society. No one piece created by Muñoz will ever enjoy the celebrated status reserved for gallery royalty. It will never come to be synonymous with what our media casually labels 'art'. Is not Muñoz's work worthy of this status? Is there something somehow wrong or inadequate with his efforts? If so, surely widespread appreciation of his work has been misplaced. Curators and patrons of some of the most respected and relevant galleries and arts institutions the world over must be in error when recognising the quality of his extensive and spellbinding installations. That his career was as succesful as it was prompts us to an understanding of his effort's appeal. The slate-grey figures, the optical floors, the ballerinas, dwarves, columns and mannequins - these physical objects are not Muñoz's art - rather the art is the encounter between viewer and object. It is the miasma of confusion, instability and psychological uncertainty. A strange silent alchemy is engendered in the encounter between the viewer and Muñoz's pieces. It exists solely in the nervous system of the viewer and it is precisely this that is the artwork of Juan Muñoz. This discussion specifically concerns itself with this subtle, sophisticated and non-physical artform by analyzing select sculptures, drawing and installations.

The range of motifs covered by Muñoz's extensive output serve as a an inventory of the obsessive creative. His manenquins and dummies are combined unflinchingly with his columns, staircases, banisters, balconies and other ephemera of architecture. His figures are human analogues rather than representations, deviating from representational scale as readily as their indefinable but eerily familiar narrative content. Finely tuned and technically consuming fabrication of resin figures, steel and wood are quietly displayed alongside cursory drawings and other remnants and echoes of human existence. As an artist who generated recurring motifs of his efforts, Muñoz had a great many. His selection of motifs appears, on the surface, wide-ranging and nebulous. Despite this, a common atmosphere is generated - Muñoz's product.

Before this discussion embarks upon a detailed examination of individual works and installations, it is helpful to isolate broader trends that occur in his output. Motifs recur, as do those of many an artist, yet Muñoz was rarely conceptually decisive enough to bookend one phase of work and start afresh with new players and abodes. There is an emergent property to his working method that reveals a body of work undeniably particular to the artist. His repeated variations of existing motifs smear one installation into another and one year's output into the next. Although this smearing can be potentially problematic when analysing an artwork in isolation, broader parentage of his work's mechanisms can be identified. First, we must recognise the influence of arcitecture and living space as Muñoz alludes to these frequently, either through props or recreation. Secondly, Muñoz depicts figures frequently, human analogues, ventriloquist's dummies, puppets and dwarves. Obviously, there are minor one-off deviations in any artist's poetic where we see experiments on new themes but in Muñoz's case they are rarely continued. They do not distract from the dominant flavour of the work for which he is best known.

Spiral Staircase

Architecture and utilisation of space by the work's narrative remained a constant source of curiosity for Muñoz. At the beginning of his career, we see that smaller work more suited for limited gallery spaces are common and it is the architectural element that came first. The almost innocent Spiral Staircase (Inverted) (1984-99) draws from the common association of architecture and the implication of a human presence. The dynamism and suggestion of movement inherent in the spiral structure are crudely rendered here but compensate intellectually with nods to art history. Degas' The Rehearsal (1877) is particularly familiar as it shares a sense of compositional disorientation while visually rewarding the viewer with the continous mathematical form of the helix; a form that implies an ascending and descending sense of movement. Interestingly, Degas' use of this form was derived from a small spiral model Degas used to study perspective.

The tones of the weathered steel are more consistent with Duchamp's Nude Descanding a Staircase (No. 2) (1912) and the sculpture's ratio of vertical to horizontal are also reminscent of Duchamp's piece. The lack of an overly self-conscious condition of finish and historical reference are hallmarks of this early work (by his own suggestion his 'first' work) showing a maturity of aesthetic and intellectual intent. However, it is through the eyes of the gallery patron that we must examine more closely the tell-tale signs that this sculpture belongs to Muñoz. That this piece is a maquette is telling. He has created an architectural feature but also an analogue of human-occupied space. There is no human to walk these steps and the uncertainty of the scale disjoints the viewer from the potential threat of the scene; the rusting walls, the steps to nowhere and not least the rickety banister that saves no-one from a fall. The mild disquiet registers. In this early peace we encounter a sophisticated mechanism that would repeat throughout his career: a sterile sense of quiet unease is produced by the simultaneous suggestion and negation of a human presence.

Hotel Declerq

Again in the architectural theme, Hotel Declerq (1986) is an arrangement of metal balcony railings situated high on the gallery walls reminiscent of the adornments of an actual structure. It's various iterations have inlcuded vertical 'Hotel' signs but not exclusively. A novel use of space, fixing the artwork higher than typical to eye-height transforms the entire wall, the gallery itself, into an inclusion of the piece. One finds it relatively simple to imagine the surreal romanticism of the 'hotel' interior evoked by the decorative rails. We are lured into picturing the incomprehensible reality within. Again playing with scale, the fittings are slightly smaller than would make a direct ergonomic comparison; no life-size entities would peer from these balconies and again we feel the simultaneous implication of humans as well as their physical denial. Without directly antagonising the viewer, a sense of unease permeates the display despite the more obvious nods to real-world references. The vertical text is perhaps unneccesary to the overall achievment but it does also serve as an interesting distortion. That is, the viewer will percieve the wording as a mirror-image inversion dependant on where they stand. The literal distortion of text is entirely believable from a point of personal experience but also serves to emphasise the still and uncanny atmosphere of the installation.

I Saw It In Paris

First Banister

Although much early work used attributes of functionality and space directly, the implication is frequently more compelling in its subtelty than the direct representation. Simply, why build a room when props will suffice? A third example of early work rooted in architectural forms are the banister / hand rails that were made in a variety of different formats. Perhaps of a more conceptual bent, these banisters rankle with their insinctive utilitarian aesthetic simply by their inclusion in the gallery space. Some are plain and straight, others are more elaborate. I saw it in Paris not only has a title that directly explains the experiential origin, it's form allows us to precisely visualise the staircase which it inspired it. In fact, for all the viewer is aware, this item could have been simply removed from its original location and mounted on the gallery wall. Other simpler railings such as the incongruously titled First Banister also have a sumptuous, utilitarian aesthetic but have the added unsettling twist of a switchblade knife mounted on the inside of the rail. The viewer, projecting their own physicality to this suggestion of utilitarian narrative, psychologically recoil from the potential injury implied by the interaction with this artwork as object but not as a gallery entity. After all, we are gallery patrons. We must not touch the work on display. This is a fairly unsubtle example of Muñoz's conceptual address of violence in his work and will be explored at greater length later in this discussion.

From a perspective of sculpture, Muñoz showed from the outset no difficulty in utilising the familiar or typical structures of interior human spaces. Banisters, railings, shelves, chairs, vents, benches, mirrors and even elevators are but some of the items incorporated into small early works as well as many later, more physically ambitious installations. The psychological familiarity of the human abode can be associated with gallery space to form the basis of interaction between patron and artwork. Typically, Muñoz's attitude to interiors evokes a sense of stillness and silence. There is a sense of emptiness - an absence of all facets of the interior other than the ephemeral. As will later be explored, the mis en scène engendered in a typical Muñoz installation implies an elusive narrative drama played out by his 'characters' and their props. The stillness of traditional sculpture (the language that Muñoz feels comfortable to employ) emphasises the lack of sound associated with human interaction.

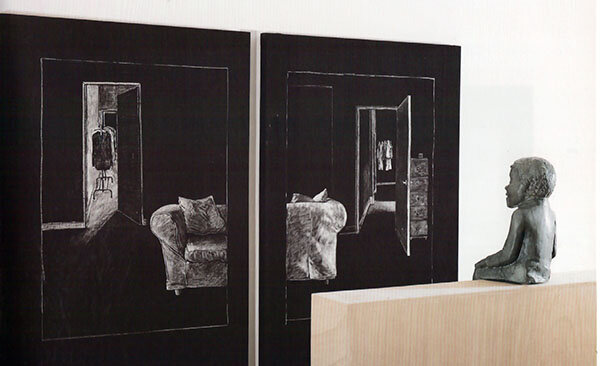

Raincoat Drawing

The Raincoat Drawings exist as an isolated exploration of this stillness and emptiness. In any analysis of Muñoz's output they are particularly instructive as they are technically suspicious compared to other, more decisive examples of artistic finish. They are among the few purely representational depictions Muñoz produced as finished works. The Raincoat Drawings are distinct in their beginning and end, deadpan in their presentation and so atmospherically repetitive that it is tempting to describe the collection of images as one work, despite their slow emergence over years. The 'raincoat' in question refers to the matt black fabric used for raincoat garments on which these seemingly simple scenes are rendered with white chalk. They depict interiors - hallways, lounges - always sparsely decorated save perhaps for one painting or rug. Chairs and setees stand empty. Every image is conspicuously free of human presence. It is the viewer alone that witnesses the empty spaces. There is a pictorial naivetè to the rendering of these images. Tone is crudely established and often inconsistent with apparent light sources. Planes of walls and ceilings are given cursory demarcation through single, often squint, lines. Perceived errors are not relevant, however. Muñoz wants us to see these as drawings perhaps, but one cannot help detect a preciousness to the depiction of certain forms. For example, there are several images where the glossy reflection of light off polished hallway floors or a wooden banister become too painterly for the establishment of his eery aesthetic. One suspects the artist enjoyed the play of light at the expense of the overall atmosphere. There is an incongruous clash of intent in some of the images. The desire to create a pleasing nod to painterly effect intrudes on the sterile subject matter. Muñoz also chose to trap each image within its own drawn frame. Sometimes this mechanism is precise and at right angles, at others this boundary is loose and freehand. Despite technical inconsistencies, definite and precise subjective inconsistencies are the purpose of these drawings. These scenes, devoid of human life, are curiously inviting to the implied presence of the viewer's own possibility of occupying each scene. The viewer is obliged to psychologically inhabit each interior as the spaces are full of potential and spacious enough to explore. Rooms and corridors are rendered either with pleasing symmetry or at classic right angles. The eye percieves corners and doorways clearly. The empty chairs look comforting and inviting. On one level, these habitats are seemingly pleasant and non-threatening. Simultaneously the viewer is rendered uncomfortable. Initially, the sparse nature of these environments raises questions. A homey quality clashes with a sterility that makes these rooms furnished almost as if for show. An institutional dishonesty stains each scene. On a more fundamental, pictorial level, the white-on-black execution of these images is unsettling, not least for the 'dark' quality of each drawing but also as it evokes the sense of a photographic negative. Combine this with the manual and precise bordering of each image and the 'snapshot' quality helps to freeze the exploration of each space in time.

Ventriloquist Looking At Double Interior

No mechanism employed by Muñoz exists without augmentation by another. Again, the smearing of techniques across platforms through repetition to produce novel combinations is apparent in these drawings. Muñoz produced paired images to be presented side by side. Such pairings invite the viewer to place themselves in the scene and simultaneously depict the empty doorway from which the viewer's psychological projection of themself ought to stand. In other paired images, Muñoz shows us an interior and then shows us the the same rendered as a third party existing on a wall, decorating another interior in which the viewer now supposedly sits. These are playful but disorienting techniques. Something of the hall of mirrors is in play and Muñoz directs the illusion. Finally, it is almost as if Muñoz cannot bear to leave an illusion or interplay in reach of being resolved without layering more complexity. In certain cases, the artist chooses to wrench these drawings out of the language of illusory depiction and place them in an installation context. In the case of Estudios para la desrpcion de un lugar (Study for the Description of a Place) (1987/88), the drawing is mounted within a bulky, unconventional box-frame construction that rests on the floor. It is canted up and against the wall by an angled wedge to aid the viewer. This piece is clearly object as much as image. With Ventriloquist Looking at a Double Interior, (1988) the dual-view is shared by the viewer with a small figure reminiscent of a ventriloquist's dummy perched on a wooden shelf. Participating in one half of the viewer's perceptual dichotomy, the dummy serves as another psychological mirror through which the viewer attempts to wrangle some sense out of the visio-spacial interplay. Muñoz does not let us rest.

Commonplace interiors and their trappings are not the only physicality of space that Muñoz has used. It is clear that he mixes the concepts of space and place as the setting in which he can arrange entities that the viewer can attempt to interpret. The innovation of his 'optical floors' provided a novel environment that divorces the viewer from a gallery-oriented context thus amplifying the sense of isolation and stillness of his 'characters' and the viewer alike. Several installations have used this motif in different ways.

The Wasteland

The Wasteland (1986) (named after T.S. Elliot's poem) insists immediate interpretation by way of literary reference. Ultimately, the suggested narrative of the piece instills its own uncanny blend of serene anguish upon the viewer. A bronze ventriloquist's dummy sits perched on a wall-mounted shelf far across the gallery space. Intervening between it and the viewer's eye is a tiled array of mathematically precise shapes. The suggestion of three dimensional structure flips between positive and negative in a hectic and distracting manner. It is the kind of visual effect frequently employed in optical illusions. It denies depth perception and provokes our cognitive visual analysis into continuous and fruitless attempts at resolution. The scene is as typically static as any sculptural installation by Muñoz yet the sense of seething movement generated by the optical floor brings a certain unhealthy locomotion to the scene. Albeit static, the mind automatically attempts to form a narrative for this display. Is the dummy stranded? Could it traverse the floor?

What, if anything, prevents us from coming to its aid? We sense that the human connection to the character on the shelf is the meat of the analysis, but it is the context of the uncanny space created by the optical floor that lays the foundation.

The Prompter

Similarly, and more enigmatically, The Prompter (1988) uses a more conspicuous version of the device. A more unabashed use of the stage is apparent. We have already sensed the tools of the showman; the hall of mirrors, the optical illusion. Here Muñoz employs the actual, figure and props to provide us with another untellable story. The stage itself is just that - elevated and undisguised, we see the platform for the optical floor raised on elegant metal struts. Confined at the edges by the stark gallery walls, the drum sitting at the furthest possible distance from the viewer is isolated and beyond reach; rendered impotent by its isolation, we once again try to ascertain the story that connects it to the installations main player. The figure of the ‘dwarf’ in the prompt box is only truly visible if the viewer attempts to peer around over the stage and into the box. It is only then that the figure appears equally impotent, without eyes or a script. Despite the inscrutable narrative, the choice of symbols to this piece evoke the theatrical - circus, freakshow or vaudeville, the viewer associates with vague connections to performance; the drum, the stage, the dwarf. Even incidental qualities such as the lighting and the beige and black finish of the installation add to these impressions. This piece is particularly useful as an example of the smearing of styles and working methods. The optical floor, figure and drum are all elements repeated in other pieces.

Winterreise

Ballerina

The largest version of this transformation of floor space into an undulating spatial threat is Winterreise (1994). Perhaps the most successful, it has the advantage of an instant human connection in narrative - we see one figure carrying another in piggyback across the mysterious changing floor. Any sense of treachorous passage is amplified by the charitable act of the carrying figure as the viewer can easily access the sense of altruism in the scene. The physical scale is grander and more inclusive. The viewer has the option of crossing the optical floor and engaging in the quietly perilous snapshot of time that this pair inhabit. The establishment of unfamiliar or disquieting space as an asset to these installations is apparent. It is important to note that they are not solely restricted to life-size installations or a literal mapping on top of gallery floors or other flat surfaces that correspond to the viewer's own physical occupation of space. In another example of Muñoz's adaptation of existing motifs, the small-scale surface has been used for selected works. The drum in The Prompter installation has the repeated optical pattern decorating its unbeaten skin. In one of a series of smaller works, a ballerina figure resides on a small plinth surfaced with its own optical floor. This is reflected by the reflective underside of the conspicuously beautiful sculpture.

So far in this discussion, the emphasis has lain in establishing the importance of the 'scenery' in Muñoz's composition. The architecture, the furniture, the trappings of human existence, the floors - these are the access points of viewer-familiarity that allow the gallery patron engage ment with the scene. The other side of the experience of Muñoz's dramas lie in the presence of humans.

To be precise, Muñoz's work employs human analogues. We have already touched upon the ventiloquist's dummies, dwarves and ballerinas. Later and more elaborate work use larger, more subtle and less theatrical figures but it is important to recognise that all Muñoz's figures can usefully be defined by what they are not. They are not figurative sculpture in the traditional sense. It is notable that Muñoz himself described his figures as 'statues' rather than sculpture. They are cartridges for the depiction of players in Muñoz's panorama of confusion. Providing a psychological point of access, the mysterious figures are essential; a powerful mechanism for engaging a viewer's innate associations that are inextricably linked with the cognitive processes that are initiated by proximity to 'flesh' and later determine social interaction. Muñoz's work provides the stage and scenery but the characters are devoid of identity to the point that we are unconsciously prompted to emote on their behalf. There are subtle aspects to the rendering of Muñoz's 'statues' that contribute to the performance as well as divorcing themselves from a casual or realist interpretation.

Typically, Muñoz's figures have the requesite features congruent with traditional figurative sculpture. We see arms and a head, usually a torso and legs. Facial features are either distorted or disturbingly theatrical, often repeated across multiple pieces to bring a forced sense of social repetition to larger installations. The multiple 'masks' that repeat throughout pieces and installations side-step mannerist decisions in sculptural finish. As do the formation of limbs and torsos across figures by way of padding out and casting clothing as opposed to defining skin, sinew and muscle. Muñoz may be credited as reintroducing the figure into contemporary sculpture despite fashion but it is interesting to note how far removed his figures are from the more traditional concerns of depicting flesh. The issue of tonality is side-stepped frequently. Muñoz conspicuously avoids colour for colour's sake and either allows earthy, natural, muted tones of the fabrication to decide the finish. Often, the figures are painted slate-grey, thus completely cutting off any emotional association with colour the viewer my have other than that of 'null'.

Detail of Conversation Piece, Three Seated Masks On The Wall, Many Times

Every figure that Muñoz made is removed from our world. It has a sense of 'otherness'. In early pieces, this was often accomplished through reference to the theatrical scene. Ventriloquist's dummies are not 'us' although their entertaining and disturbing animation show how clearly they aspire to be. The Ballerinas (1989) are removed in scale, circumstance and rendering to the point that they become ornamental more than empathically accessible. In later works, Muñoz uses the figures of dwarves to insist a sense of humanity despite form being significantly removed from that of the average viewer's experience. Simply put, Muñoz's figures are as human as they need to be and no more. Even in later work where the figures appear most like those of adult human beings, subtle distinctions serve to quietly remove the pieces from our universe and isolate them in their own dramas.

Arab

A single work, Arab (1995), is useful to isolate as an example of a piece that exhibits common mechanisms inherent in Muñoz's address of figurative forms as it is, unusually, unsullied by peripheral architectural forms or utilitarian props. In particular, evidence of manufacture is useful to examine. The figure sits cross-legged and heavily draped in it's clothing. The head-dress alludes to an ethnic origin despite the comical structure of drained clay solution from a coffee filter being planted squarely on the head. The casting of the polyester resin figure shows little sign of a mold-making process. Seams are well disguised in the overall finish - that of a sandy hue reminiscent of outdoor, dry spaces. Facial features are simplified and calm. The hands are crudely rendered yet succeed in generating an overall air of concentrated intensity. Indeed, the figure's demeanour is contained to the exclusion of the viewer. This figure is engaged in it's own business. It is highly absorbed.

The attitude, the finish, the supposed ethnicity and the self-absorbed engagement all serve to promote that air of 'otherness' that simultaneously alienate and invite the viewer to the gallery encounter. If the experience of human closeness to sculptural facsimile can be compared to a mirror's reflection - the piece presents a psychological proximity to what it is to be a person but then precisely and deliberately fails to reflect back at the viewer. As Muñoz concisely stated himself, "My characters sometimes behave as a mirror that cannot reflect. They are there to tell you something about your looking, but they cannot, because they don't let you see yourself." By means of 'otherness', Muñoz's figures deny any camraderie with the viewer.

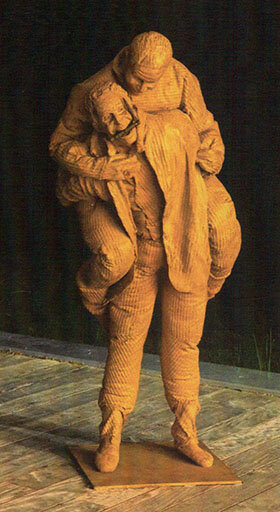

Single figures such as Arab are a rare manifestation in Muñoz's repertoire. Typically, we are more likely to encounter drama and interaction. In the case of Piggyback with Knife (2001), we get both of these. Complex and intruiging, the initial encounter with this piece is deceptively childlike in the way it engages the viewer. The simple experience of a piggyback evokes childhood bonds, memory of friendships and horseplay.

Piggyback With Knife

To find adult figures engaged in this activity provokes a flash of the bizarre and aberrant. An implied deviance starts to take shape. Are these figures drunk? Are they playing or is there something more unsettling in their relationship? They are unified in their exterior. Unusually for Muñoz, a vibrant ochre hue serves to morph these two figures into one. The colour evokes unease and the resin surface is heavily crenellated across attire and features with the exception of the faces. The faces are identical (a cast of Muñoz's brother, Vicente which also is duplicated in other pieces) and hold the same manic, strained expression - suspended somewhere between anguish and laughter. As ever with Muñoz, the subtleties slowly insist themselves and the confusion flavours the unease. We note the twist in the standing figure's spine - this weight he carries is harder to bear than most of us would like. A bronze lock-knife is gagging him, the blade perilously close to his cheek as his hands are occupied by the weight he carries. His companion bears down on his left ear, either whispering or screaming. We dread the silent narrative in front of us. This is no equal or friendly relationship. One senses the irate command, the mocking superiority of the figure being carried by his twin, now reduced to a pack-animal. It is worth noting the smearing of common motifs across Muñoz's repertoire. Piggyback with Knife exhibits the figure, the padded out clothing hinting at limbs rather than defining them, the knife, the multiple face and of course, the piggyback itself, an often repeated drama.

Piggyback With Knife (detail)

Of course, unlike Winterreisse, where one figure charitably helps another navigate an optical floor, this scenario is introverted and non-reciprocal. The formal qualities of the piggyback drama as sculpture are impressive. To unite two figures as one is a novel and satisfying innovation by Muñoz. We are still looking at figurative sculpture standing on two legs yet we have all the layered connotations of interaction concentrated into this efficient package. Piggyback with Knife is a dark interpretation of the playful.

Most frequently, Muñoz employs multiple figures in his work. In any given piece, each figure is of the same 'species'. That is, regardless of formal choices that have decided the facial features, bodily structure or surface patination of each figure, they ultimately share enough anatomy in common to be recognised as belonging to the same tableaux. From a technical point of view, this is advantageous when analysing the methods of their construction. For example, his full figures are fabricated by resin-cast molds following an assemblage of clothes and fabrics that are stuffed and padded to form vague approximations of the supposed fleshy anatomy underneath. Elbows and knees exhibit gradual curved bending of the limb joints rather the usual decisive axes of articulation. Hands are often fashioned in the same manner using gloves. Heads are cast in multiple and later placed on each new version of the form. Muñoz's figures appear to be cartridges. Fabricated with unsentimental rigour, it is often only the patination or choice of colour that harbours evidence of aesthetic consideration. Each finished figure would appear banal and empty in isolation but it is the contrived absence of decorative appeal in the sculptural process that allows room for the full force of their implied narrative when the figures are united in their careful coreography. The narrative itself is never within our reach, however - rather, it hints at a possible human interpretation but never fully delivers. We feel the narrative in the air but cannot fully rationalise what we experience. Again, this is Muñoz's art. It is in the air, not in the objects we see.

Conversation Piece

A typical and particularly successful example of an installation comprised of figurative elements in interaction is Conversation Piece (1996). There are numerous different iterations of this work. Multiple figures have been cast for interior and exterior display. Some more casually curated in touring exhibitions, others installed permanently as public art bronzes. Despite the variations, the central drama is repeated across all. We observe figures, animated forms that posess a peculiar dynamism - their rotund bases suggesting a rolling energy of movement. Their padded torsos flex according to their spacial and social rôle. Two figures are absorbed in discourse. A third yearns to engage with them yet is tethered under the control of a fourth, itself frantically clutching to wire reins. A fifth is peripheral to the intensity of the exchange, usually set some distance from the others. It is with this fifth figure that the viewer most instinctively associates. As we stand at the edge of this mysterious interplay, we too attempt to decipher what we see before us. Again, as in Piggyback withKnife, we instinctively assume engagement and understanding of the scene before us as our childlike recognition of interaction commands our observation. The anatomical 'otherness' of the players in this scene reject a rational, conscious interpretation of the drama yet the familiar arms and blighted faces encourage us in our efforts at a primal, associative level. That Conversation Piece has been so often reworked and edited indicates the importance of this form of interaction within Muñoz's installation poetic. For it is not merely the sense of interaction and the atmosphere of inclusion and alienation that it generates, it also punctuates Muñoz's output with particular emphasis on interaction by the gallery patron, the viewer themselves. In this work, as in others, the root to experiencing the installation lies in identification with the protagonists. Simply, we feel our own physical and psychological presence in the work to be as valid and vulnerable as the figures themselves. The scene before us illicits vague and instinctive recognition of human presence in the here and now, therefore we are subject to the parameters of the theatricality we observe. We are subject to its conditions, its possibilities and its threats. We include ourselves alongside these figures so we play by their rules. If we do not fully comprehend what is transpiring we automatically feel unsease. After all, there may be danger here. This instinctive dread is often augmented by subtle intimations of physical violence that Muñoz employs throughout his installations. However, despite the engagement of our innate responses to interactive social situations by the work, it is the natural state of sculpture in the gallery that contrasts and jars so schockingly with our initial appraisal of the work. Simply, we are observing static, frozen time - silent and still. The viewer has the isolated status of gallery viewer that marks them out from the characters Muñoz creates. They may enter, observe, move around and through the installation, and eventually leave. This sense of freedom, of conscious decision and simple understanding of the accepted rôles of artwork and audience maroon the viewer in their own humanity. The viewer sees figures but can never be one of them, they can never fully appreciate and engage in the scene they observe. The viewer is condemned to be isolated among sculpture. The silence fills the air and punctuates the disconcerting flipping between identification and exclusion.

Towards The Corner

As Muñoz's understanding, experimentation and utilisation of this jarring status between viewer and piece evolved, it intensified. The possibilities of larger scales and the scope of grander installations concurrently initiated work that increasingly generates this quiet but seething interplay between artwork and human. Towards the Corner (1998) again features a constellation of figures. They are arranged in casual positions on a sparse wooden structure reminiscent of a sporting event or possibly an outdoor theatre - clearly designed for spectators. Seven figures with identical laughing, asiatic features are our spectators for, as the arrangement faces into the corner of the gallery space, the viewer instinctively proceeds around the installation to face the figures. The observer is seduced into the arrangement to become the observed. We see recurring tactics in play. First, the sense of 'otherness' of these figures is established not just by the sculptural fabrication but particularly the choice of identity imposed upon them. Despite the relatively realistic garb of the figures, ethnicity and humour serve as the distancing mechanism.

detail

The asiatic features, cast in multiple are laughing and smiling freely at the viewer. They share a joke or react to a performance that remains hidden, secret among them. Their grey hue expressly forbids an emotional reaction to colour or tone and serves to unify their presence , particularly when contrasted with the natural earthy texture of the wooden stand. Finally, the analysis of the work can only be complete with an analysis of the viewer themselves. The viewer may regard these figures in the rôle as gallery patron but the installation is activated by their presence as a necessity. This status is thrust upon us by Muñoz. We did not expect nor ask for this rôle yet it is ours to handle. Again, the silence and stillness of the installation jar with our mobility through physical space as well as time. We choose how long to engage with these players. We choose when to end the encounter and no longer suffer under their incomprehensible mirth. Again, this interplay is in the air, travelling between us to the 'statues' and back again, instinctive in incept and never to be resolved. Notably, this piece is dependent on the architectural setting - where the viewer first encounters the work and then navigates their relation to it.

The asiatic figures are most spectacularly repeated in Many Times (1998). This installation has the flexibility of endless configurations. Standing figures smile and laugh, some with simple, casual gestures of the arms. Commonly the figures stand in groups, interacting within their own clusters, universal in their shared laughter. It is the viewer who is isolated - excluded from the interplay despite their freedom to move and observe through the silent throng. Subtle enhancements to the figure's status as 'other' is amplified by the scale of the installation. The figures have no feet, giving the unnerving impression that the gallery floor is possibly rising up through the mass of their bodies - maybe even the viewer's too. Do these figures somehow occupy a different physical reality where the fabric of the building itself is different from what we are accustomed to?

Many Times

Many Times, Washington DC, 2002

Furthermore, the reduction in height of these figures is apparent immediately. We traverse this strange playground as victims of our own unnatural physical scale; giants among the characters who are clearly enjoying themselves more than us. As in Conversation Piece the various iterations of Many Times are subject to curatorial tinkering, some of which are, by their extremity, capable of drastically altering the impact. Many Times is usually displayed in large open galleries that allow ample room for viewers to mingle with the figures. An iteration of this installation at Washington DC's Hirshhorn Museum featured an empty room in which all the figures were standing on a balcony level above the viewer.

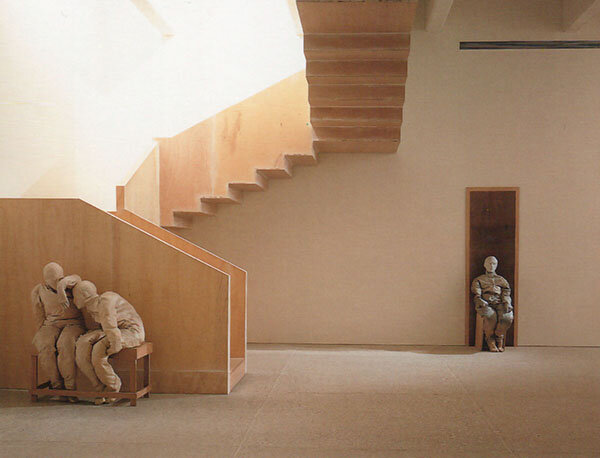

Had Muñoz been available for consultation, such curatorial decisions may have been curtailed or expanded depending on whim. As Muñoz's status as a contemporary artist shifted into that of an acclaimed and significant one, the technical and financial freedoms associated with artistic success allowed for ever grander and impressive work. Despite these freedoms, Muñoz preferred to allow the context of the gallery to inform his installations. More significantly, we can see that his installations became an expression of both fundamentals within his ouvre identified at the beginning of this discussion – the figure and the trappings of architecture. In the case of the New York Dia Centre exhibition, his regard for architecture was allowed free reign. Muñoz, controlled the space so utterly that new walls were erected and textured, complete with sculpted doorway 'blanks' alongside windowless shutters.

A Place Called Abroad (detail), Dia Center, New york, 1999

A Place Called Abroad, detail

Figure pieces were reformatted to punctuate the space that precisely guided and manipulated the viewer within Muñoz's corridors – installations within an installation. An ambitious and audacious use of gallery space, the Dia Centre success as well as ever-expanding multiple figurative pieces such as Many Times evinced a repertoire important enough for Muñoz to be invited to make work for what would prove to be his most ambitious installation.

Double Blind, Tate Modern, London, 2001

Double Blind, detail

The Turbine Hall of London's Tate Modern provided a huge blank slate for Muñoz to compose a new installation. Entitled Double Blind (2001), it combined architectural curiosities with figurative elements to create an intoxicating, multi-layered gallery encounter. The combined whole of Double Blind serves as a roll call of Muñoz's motifs. Figures with their props, shutters and vents, elevators, apertures reminiscent of his optical floors – these motifs combined in a truly novel architectural construction. One of the principle challenges for utilisation of the turbine hall space is it's sheer physical scale. Muñoz, tackled this dominance by allocating vertical partitions unnaturally linked by 'skylight' apertures. From the mid level viewing platform, the installation appeared as a flat expanse with square holes leading to a dark underworld. Two elevator cabins periodically emerged, rose to the heights of the ceiling and then descended into the dark rhymically. The positioning of these square 'floor windows' punctuates the scale of the hall as well as optically complimenting the exterior of the installation as a whole. Viewers feel the length of the vista when observing the installation from this walkway.

Double Blind, detail

The ground level underneath is a covered, dark and ominous space. Supporting pillars hold the ceiling overhead and the only illumination available comes from minimal electric lighting, the elevator 'shafts' and other skylight apertures. However, there is a third unattainable and mysterious level between this gloomy 'basement' and the lofty heights above. This mid level exists as the abode of Muñoz's figures. Some are in playful interactive groups, others stand alone. Some exhibit a mysterious industry, carrying bundled fabric or light sources. All are engaged in their activities. Their mid-level environment hold the trappings of bland, functional architecture – shutters and vents seemingly at odds with the purity of the empty void above. The entire structure and it's mysterious inhabitants superbly answer the question of practical exhibition within such a large space. Creating multiple views and experiences, it conveniently allows for a large volume of gallery patrons without compromising artistic intent. The viewer experience in the gloom is one of dislocation and uncertainty. Intruigingly, the figures above are among the most expressive and human-looking Muñoz created. The sense of 'otherness' is this time achieved by their location. On this occasion, Muñoz has succeeded in allowing the very architecture of his scene to disjoint his players from reality. Installations within the larger installation, their silence and stillness maroons the viewer below in the dark. However, typically for Muñoz, he does not allow our sense of isolation to rest for so long as to become conscious and tangible. He jars us subtlely into enough of a common link with the creatures above as to query our association with them. Before long, an elevator carriage arrives to closed gates. The stillness is interrupted with these crude chronometers, marking periods of time in this atmosphere of indecision. The heady cocktail of impressions – the confusion and disquiet is diluted with a sense of perverse serenity and the uneasy interaction of others nearby, whether they be flesh or polyester resin.

Whichever flavour of incomprehensible unease generated by Muñoz's work depends on the viewer and the piece in question. Whether it be confusion, stillness, alienation or isolation, a subtle implication of violence is inherent in a great deal of his output. The early balconies were informed by drawings featuring buildings aflame. Early constructions like the banisters and wooden steps of Jack Palance à la Madeleine (1986) featured the inclusion of a switchblade knife similar to the later Piggyback with Knife. Even some of the conspicuously beautiful Ballerinas featured blades or sharp hooks for arms.

Hanging Figure (After Degas)

When examining the suspended Hanging Figure (1998), Muñoz uses a bright yellow tether protruding from the mouth suggesting this hanging figure (reminiscent of one of Degas acrobats) may be hanging from its own viscera. The hollowed-out eyes and sealed mouths of some of his figurative work suggest actions occuring to these silent characters – some violence done to them perhaps that they are unable to protest. Even non-figurative installations such as the crudely welded Loaded Car (1998) or the sumptuous wrecked train carriages of Derailment (2000-2001) imply a disaster narrative. Violence - perhaps deliberate and often intrinsic - pervades Muñoz's work. Even the nameless provocation that seeps through the air and illicits a rebounding unease from the viewer is analogous to random assault. Provocation and isolation are the ethereal siblings of psychological violence.

Despite his insistence on a lack of perceived identity regarding his Spanish origins, one cannot help but query the development of the artistic mind in the shadow of Franco's repression. Secrets and unease infest Muñoz's repertoire as much as the aridity of Spanish contemporary art in the wake of the fascist regime. Motif's such as the dwarves often incite a banal critical association with Velazquez merely by Spanish cultural labelling.

If not borne of political or societal underpinning, perhaps something in Muñoz's childhood character is associated with conflict, either as victim or instigator. We know he was expelled from school and later ran from home. Are these indications of frustration and rage in a developing mind? Has the past stained the machinery that makes these artworks capable of challenging, provoking and insisting themselves in less than comfortable combinations? In interview, when queried on the presence of violence in his work, Muñoz replied that he had once gone through an obsessional phase of carrying a switchblade knife and touching it in his pocket habitually. Upon recognising a developing neurosis, he consciously and deliberately substituted the knife with a deck of cards. His final comment on the subject, 'I don't know if I am answering your question' neatly provides a coda to a profoundly illuminating piece of pyschological auto-correction as well as a semantic parallel to his artwork. If violence and conflict once held sway over Muñoz's thoughts, his capacity for subtlety and theatrical invention exerted themselves over a potential for destructive thinking. Interests such as architecture, art history and conjuring provided sustenance for a highly intelligent mind as well as providing structure – checks and balances for one wary of antagonistic impulse. Even still, magic and trickery require a subdued captive audience prepared for manipulation – as do the victims of violence. One may speculate as to the prevalence of violence within the contemporary Spanish cultural character. Interestingly, recent Spanish cinema provides a parallel to Muñoz's output. The success of Guillermo del Toro may rely on a fantastical ouvre that frequently references Franco's oppression but is also prone to bouts of shocking bloodshed and the grotesque among scenes of great beauty. The last five years have seen a surge in Spanish-language horror / fantasy cinema such as Cronos (1993), Rec (2007), and El Orfanato (2007) that are enjoying international acclaim. Muñoz's predilection for the mis en scène is rooted in the skills of the conjuror and the trickery underpinning the theatrical. This is a talent shared by film-makers. Muñoz's identity as an artist is coloured by theatricality, illusionism and the tendency to control the scene before the viewer. His more than casual interest in conjuring doubtlessly stems from this lurking circus ringmaster – his desire to provide spectacle and narrative for an audience. His brief forays into the written word or sound pieces (such as descriptions of card tricks being performed) also concern themselves with illusionism and the generation of uncertainty. Even if Muñoz was able to steer artistic intent away from violence directly, the atmosphere produced by his sculpture has parallels with violence, conjuring and showmanship; the viewer is effected indiscriminately and, although apparently passive in the encounter, is the sole benefactor or target of the encounter's purpose. The dialogue between his installations and the viewer feels reciprocal but ultimately the viewer does not benefit or attain clarity.

Only a few months past the installation of Double Blind saw the untimely passing of Juan Muñoz. One may speculate as to the nature and scope of works possible had he lived and continued to develop his poetic. Access to physical scale suggests an increased manipulation of architectural forms to augment the gallery experience – to more fully manipulate the viewer. Regardless of unrealised potential, it would seem likely that common motifs and common intent would recur.

Muñoz's legacy is curiously isolated in art history. His emergence as an artist occured in a relatively arid cultural context. When formulating his first pieces, Spain offered little artistic camaraderie. His insistence on reintroducing the human form was not fashionable. Architectural and experiential concerns have distant affinity with Richard Serra for whom Muñoz expressed admiration – indeed, it was Serra who delivered a eulogy at Muñoz's funeral – but Muñoz's legacy, although lauded, seems to inhabit a quiet parallel universe comparable to his evocative installations. However, the notion of sculpture and installation becoming more experiential continues to echo. Gormley's audacious elevation of the floor in Moscow's Hermitage Museum in order to allow the viewer to equate the classic marbles with their own flesh is reminiscent of Muñoz's intent. Kapoor's compressed air gun firing wadded maroon matter is a crowd-pleaser – the artist the ringmaster. That Muñoz died on August 28th 2001, so close to the momentous events of 9/11 curiously bookends his career on the far side of a milestone in the zeitgeist, before cultural paranoia and perpetual war became the norm.

Muñoz's work continues to travel the world in numerous retrospective exhibitions. His installations, sculptures and drawings translate easily into different cultures. This is because they rely not on a political or social context. Rather they address and manipulate fundamental, hard-wired processes within all humans that are essential to social discourse, empathy and projection. Subtle, unsentimental use of materials are necessary tools to engender the psychological complexities that bounce between viewer and object. Muñoz's quick mind and natural guise as a trickster ensure that this interplay remains unconscious and indecipherable, not commonly quantified by mere language. Mirrors and shutters, banisters and balconies – these props are not sculptures. They're just props. The physicality is the mechanism and the art is in the air.

___________________________________________________

Bibliography

Benezra. N | Viso. O.M (2002) Juan Muñoz, Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago

Causey. A. (1998) Sculpture Since 1945, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Giménez. C | Breslin. D (2010) Juan Muñoz at the Clark, New Haven, Yale University Press

Kelly. K. (1999) Juan Muñoz, New York, D.A.P

Krauss. R. E (1977) Passages in Modern Sculpture, London, MIT Press

Lingwood. J. (2001) Juan Muñoz - Double Blind at Tate Modern, London, Tate Publishing

Morris. F. (2006) Tate Modern - The Handbook, London, Tate Publishing

Neri. L. (1996) Silence Please - Stories after the works of Juan Muñoz, London, Thames &Hudson

Neri. L. (2004) Juan Muñoz - Selected Works, New York, Zwirner & Wirth

Tosatto. G | Brilloit. C (2007) Juan Muñoz – Sculptures et Dessins, Grenoble, Actes Sud / Musée de Grenoble

Tucker. W. (1974) The Language of Sculpture, London, Thames & Hudson

Wagstaff. S. (2008) Juan Muñoz - A Retrospective, London, Tate Publishing